John W Miller is a writer and documentary filmmaker, originally from Brussels, Belgium, who now lives in Pittsburgh. He left the Wall Street Journal in 2016, after more than a decade covering European business news, to make a documentary for PBS about the town of Moundsville, West Virginia.

He’s currently working on his first book, about legendary Baltimore Orioles manager Earl Weaver.

You can read John’s full bio here.

*

Steve – What was the first baseball game you went to and what do you remember about it? What are some of your most significant baseball memories?

John – The first game I remember was in the summer of 1985. I was seven years old and living in Brussels, Belgium, where I was born and grew up. My parents were musicians from Maryland who’d settled in Europe, but they took us back to visit once in a while. I had a bunch of uncles and they thought it was a good idea to re-Americanize me and take me to ballgames. I remember walking into the massive red brick Memorial Stadium and trooping up the ramp and seeing the green of the field for the first time.

I’m pretty sure it was this Sunday afternoon game between the Orioles and the Kansas City Royals. The Orioles won 6-4. Mike Young hit a homerun. I remember the green grass, the Orioles mascot, and the clean bugle sound of “Charge!” For a boy who spent his time in rainy Brussels, it was a life-changing moment. I’ve never fallen out of love with baseball since that day.

Steve – And what was the first US election you voted in? What do you think have been the most important changes to how our politics operates since then?

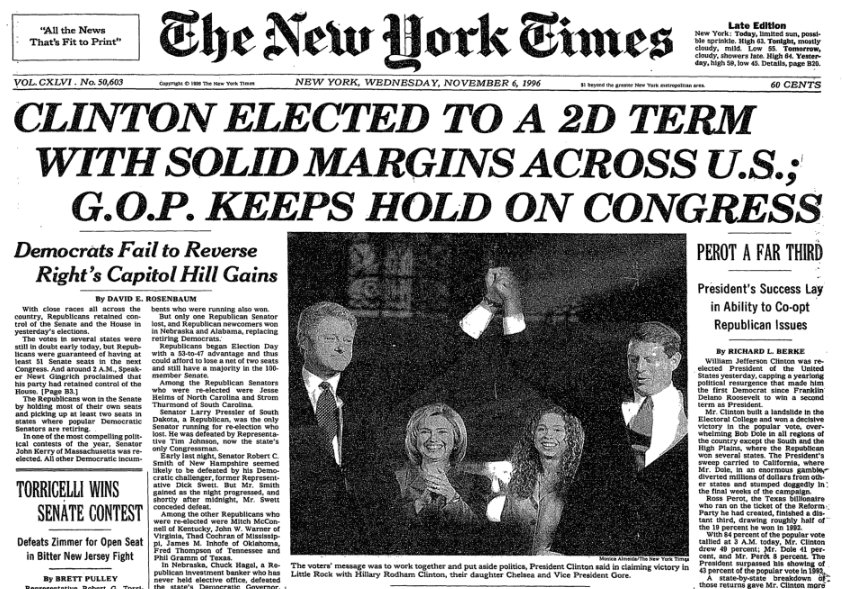

John – I’ve always been conscious of my citizenship, even as a French-speaking Belgian kid. I voted as soon as I was old enough, in 1996. I was really into politics as a teenager. From across the ocean, it seemed very exciting. I borrowed books from the U.S. State Department library in Brussels. I listened to speeches on Armed Forces Radio. There really was much more bipartisanship back then. Most of the U.S. politicians when I was a kid had experience fighting in World War Two or Korea. They felt a solidarity with all other Americans, even political enemies. Now that’s gone.

*

Steve – You left the Wall Street Journal after more than a decade covering an interconnected global economy and, like me, you grew up outside the US before coming to live here.

Were you as mystified as I was at how little importance foreign policy has traditionally had in American electoral politics? Is the war in Ukraine – and the reporting of people like Evan Gershkovich – changing that? And what do you think will be the key issues for voters heading into the 2024 election cycle?

John – America’s always been inward-looking. It’s the nature of such a big country. And it doesn’t have to be, because this country has always had such wonderful journalism that covers the rest of the world. I think the only real issue for voters in 2024 is Trump and the extremist movement in the U.S. I don’t think Americans care about Ukraine as much as they care about getting American democracy back on its feet.

Steve – How would you assess the quality of politicians and political discourse in your own state of Pennsylvania? Last year’s contest for Governor highlighted perhaps one of the widest contrasts between major party candidates in the country, but that kind of partisan division is obviously repeated across many states and local governments. Do you think we might ever get back to anything approaching a consensus view of what politics is for, or is the toothpaste out of the tube and we’ll just have to find a different way to co-exist?

John – I think local leaders in the U.S. are generally more competent, intelligent and authentic than national politicians. Josh Shapiro, the Governor of Pennsylvania, is an example of somebody who might not have the stamina and fund-raising ability to win a national race, but is a solid public official. Larry Hogan, the departed Republican Governor of Maryland, is another example of that. Those are the people who give me hope. I don’t see how national politics stop being a mess. I think in the long run, the U.S. moves for a federalized system. I don’t really see how California and Alabama are still part of the same country in 2100.

Steve – Your PBS documentary Moundsville is a beautifully observed, affectionate picture of a small-ish town and its residents – a view of civic pride, nostaglia and economic realism that could easily be replicated in many other similar places.

One of the things I particularly loved about it (apart from the wonderful Marx Toy Museum) was that it wasn’t primarily about politics, but it offers a picture of how resilient and co-operative ordinary people can be, regardless of what’s happening around them. In making it, was there anything you learned about America, past and present, that gives you optimism for the future?

John – Thank you for the compliment. Yes, the local political talent I described above gives me hope. And in a place like Moundsville, there are young leaders who’ve boomeranged after living elsewhere. Even though they tend to be younger and more progressive, they get along with their older, Trump-supporting political colleagues.

*

Steve – Moundsville, and other projects you’ve worked on recently, are fundamentally about conversations, and how we can best try to understand each other. Is that becoming more difficult because of how media is changing? We talked about how we had both worked on newspapers at what we thought was probably the most disruptive period in the industry’s history – but now it seems that AI is about to usher in a different way of generating content.

When we met up for a drink after the game, you were talking about how what readers want now is something they’re seeing for the first time, and that can’t be found on a search engine. That’s a worthy aim, but how does it pay the bills for media organizations? And if it doesn’t, how – to rehash an old newspaper challenge – do they give people what they need alongside what they want?

John – There’s no easy answer to building a profitable business model for local newspapers. If you or I knew what it was, we’d be rich. The U.S. news ecosystem is broken, and I don’t see how it ever gets put back together the way it used to be. I think there should be some sort of subsidy for local news orgs, maybe a tax break, that encourages entrepreneurs to start new media companies. But ultimately local people need to create new storytelling initiatives that become institutionalized into new forms of journalism.

Steve – On the subject of media, it seemed like the end of an era recently when the New York Times said it was shuttering its sports section and rolling its coverage into The Athletic, which it bought last year. What do you think about the rise of digital sports sites – many of which have been driven by fantasy and betting data and stats-based niche content, as well as talk-radio style opinion silos?

John – I don’t love the normalization of gambling in sports media, but I don’t spend much time worrying about sports journalism. There’s plenty of it.

But I will highlight a problem, and that’s that it has fallen prey to the curse of celebrity journalism, where the subjects, the athletes, and their employers, make so much money and have so much status that they dictate the terms of engagement with journalists. Have you listened to post-game interviews with ballplayers? They’re almost always so boring. And it’s because reporters are scared to ask anything that’s not a terrible cliche.

Steve – You recently won a New York Press Club Award for an excellent article on little league baseball which generated plenty of reaction. In it, you wrote that “…Baseball is becoming a mostly white country-club sport for upper-class families to consume, like a snorkelling vacation or a round of golf.”

It led you to write a follow-up on how to get American kids to fall in love with baseball (again).

Where is the game generally headed, do you think? Obviously we’ve had the recent rule changes which have certainly made games shorter, created more action and seem to be attracting more fans to the ballpark.

John – Baseball’s too great to ever die, as long as we have a semi-functional society. But its popularity waxes and wanes. And it does need to be entertaining for people to enjoy watching it and want to play it. Part of that is creating a game that has rhythm and doesn’t take forever. At the Major League level, the pitch clock helps impose that rhythm. At the youth level, that requires strike-throwing and good catch-playing, which can only happen if kids plays catch in their backyards. So, go play catch, kids.

Steve – But if MLB’s aim is to win younger fans away from the NBA, or e-sports, for example, just cutting an hour off the time of a game isn’t going to do it; it has to be, as you say, an outreach to help kids love the game, independently of their parents. What does MLB have to do to secure that audience stream in the future?

John – Just make the sport fun to watch. I don’t think you can impose a sport from the top down. It has to be a desire that exists independently in the hearts of millions of boys and girls, like it existed in our hearts when we discovered baseball.

*

Steve – Finally, past and present collide in Baltimore. Your latest project is a book about legendary Orioles manager Earl Weaver. What remains so irresistible for you about Weaver after all this time?

John – Weaver is a foundational character in baseball history. As I wrote in my obituary for the Wall Street Journal, he changed how baseball is played and watched. He was the first manager to apply a rational, statistics-based approach to managing and winning baseball games. And he was also friggin’ hilarious.

Steve – Also, the present-day O’s could well be on the brink of something very special; with Brandon Hyde’s team riding a perfect storm of overachieving ahead of schedule and having an absurdly well-stacked collection of prospects. How do you see this season and next playing out, and what pieces do they still need to add?

John – I don’t think they’re overachieving. They’re really, really talented, and at that sweet spot of enough experience to compete but not so many years in the big leagues that they’re jaded and surly and in love with themselves. Also, they have Adley, the greatest young clubhouse leader in baseball.

I think they’ll make the playoffs this year and for the next four or five years; and win one or two World Series. They’re the new Braves.

*

You might also enjoy these other Conversations:

Ian Nicholas Quillen – Over/Under

“As you probably know, Earl Weaver engineered moneyball before Sabermetricians existed, and he did it only based on an intuitive sense of what the probabilities were rather than statistically significant data. That led to some flaws of course; but his general intuitive sense of probability was amazing.”

*

Danny Knobler – Relief

“[Sports journalism’s] relationship with the audience is an interesting point, and can be both positive and negative. Through e-mail and social media, it is much, much easier for readers to respond. That brings on a lot of sniping, but it can also result in feedback that helps the writer improve stories or better target stories that are of interest to readers. And the quick availability of statistics, records and archives through the internet means a good reporter/writer can include facts and tidbits that weren’t accessible in the past.”

*

Rose Jacobs – Spartan Strong

“To generalize from my conversations with individuals [in Germany] — which probably overstretches their broader interpretability — even the Americans most engaged and informed about Ukraine are not nearly as engaged as the average German… To the Germans, this feels existential; to the Americans, it’s still distant. Here in the US, the more pressing issue often seems to be whether Trump’s going to be indicted.”