*

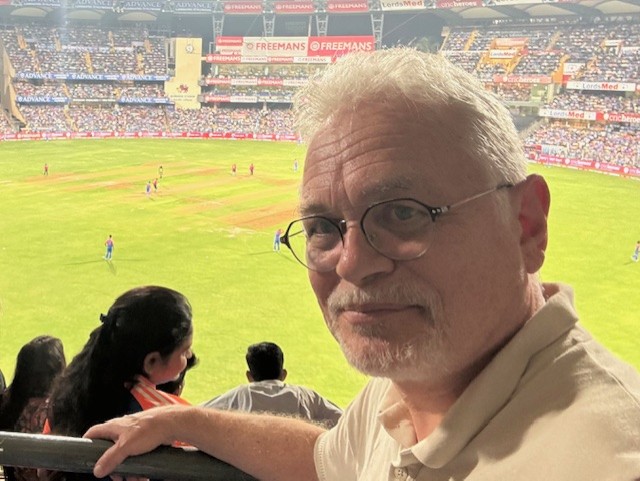

Chris Birkett is an award-winning journalist and broadcast news producer who now teaches and researches in the field of political culture and sport in the United States. He’s the author of Bill Clinton at the Church of Baseball – The Presidency, Civil Religion and the National Pastime in the 1990s.

You can read his full bio here.

*

“There’s a narrative arc that unites both baseball and politics – and that’s the erosion of symbols, institutions and ideals which once bound people together.”

*

Steve: What was the first baseball game you went to and what do you remember about it?

Chris: I first watched professional baseball In Toronto in 1983 – the Blue Jays at the old Exhibition Stadium.

I barely remember the game itself, but what stayed with me was “the Wave,” the rhythmic craze that was sweeping through North American sports stadiums at that time. I’d been part of ritual chanting and swaying at football matches in the UK but experienced nothing like the synchronized choreography of bodies and arms which rippled around the ballpark that sunny afternoon. I am not a fan of it these days (it’s an irritating distraction and thankfully not as common), but at the time I must admit I was impressed.

A week later I took the train to Montreal for an Expos game at the Olympic Stadium. No wave, and a much smaller crowd, but I remember the bilingual announcer and one player, the catcher Gary Carter, who was clearly the fan favourite. The following year I witnessed baseball in the US for the first time, when I went to Shea Stadium in New York.

My memories are vague: the Mets’ huge multi-coloured electronic scoreboard made an impression (I was accustomed to the hand-cranked scoreboards of cricket) and I thought the “charge” bugle call and response was great fun. But again, only one player sticks in the memory, Daryl Strawberry, and that’s because I thought at the time he sounded like a character out of a Roald Dahl book.

Steve: I’m pretty sure you’re the only one of these Q&A subjects – that isn’t a professional sportswriter – who has visited every MLB team. You’re certainly the only Englishman. Tell us about that quest.

Chris: I suppose my ambition to go to every MLB club was driven by professional curiosity fortified by a dash of middle-aged self-indulgence. In 1998 I was approaching forty and had been covering US politics since Clinton’s first presidential run.

Back in 1992, I’d been sent on one of those “test-the-temperature-of-America” trips that the BBC loves during election campaigns – a sweep across the country that took in Los Angeles, Oregon, Kansas, and New York. The only ballgame I went to on that trip was in a small rural community, Elkhart, on the Kansas-Oklahoma border, which had a team in the Jayhawk League, a summer league for rising collegiate talent.

The whole town had turned out, and it provided us with brilliant material for an authentic mood-of-the-voter piece, all in the setting of America’s iconic pastime. And what was apparent even then from those we spoke to (most of them supporters of the maverick independent candidate, Ross Perot), was the gulf in trust between those in middle-of-America communities like Elkhart, and the politicians in Washington who were supposed to represent their interests.

By 1998 I was in Washington myself producing the BBC rolling TV coverage of the near- implosion of the Clinton presidency following his affair with Monica Lewinsky. The story both excited me (how could a heady mixture of sex and politics fail to) and to be honest, bored me a little too. It was clear that Clinton would survive his impeachment.

As I sat through hour-upon-hour of Senate hearings, I yearned to get beyond the Beltway, to be out on the road as I had been in ’92, trying to capture the intangible “real America” of journalists’ imagination.

One of my colleagues in DC was another Brit. Simon had been watching baseball televised on Channel 5 in the UK in the middle of the night. I’d been to a smattering of MLB games during my regular trips to the US since the early eighties.

Together we planned what we thought would be the most fun way to capture “real America” as we saw it: we would take annual baseball road trips and try to go to every major league franchise.

It wouldn’t be a work thing – just two middle-aged blokes imagining ourselves as Jack Kerouac – the highway and the ballparks of America stretching out ahead of us. Neither of us had any domestic commitments at the time which would get in the way – and we were both slightly obsessive characters by nature. We liked collecting things – ballparks would do. The following year the quest began – Milwaukee, Chicago, Detroit and Cincinnati were our first stops. The Elkhart Dusters had a lot to answer for.

*

While on the road, we didn’t take photographs – the idea of a smiling picture in each stadium never occurred to us. We were just two middle-aged men living the moment – windows down, worries gone. We harvested the freebies, picking up our fair share of giveaway junk: bobbleheads, rubber ducks with players’ heads, caps, bar towels and, my favourite, a paperweight of Veterans Stadium given to those of us at the Phillies’ final game in the arena in 2003 (below). It’s all stacked on the shelves in my study.

And, of course, I’ve kept the only major league ball that I snared – it was a foul ball secured in a late-night extra innings game in Phoenix when the Mets were in town and we were the only fans left in our section of the stadium. I didn’t even have to compete with anybody; I just strolled down a couple of rows and scooped it up.

*

Steve: Who was the most impressive player you’ve seen in person?

Chris: The most impressive thing for me is not individual players – when you’re watching one game out of 162, and then immediately moving on (which is the nature of a road trip), the chances are that you are unlikely to see a marquee player have a marquee game on any given night. It’s a cliché but in baseball even the best players fail most of the time.

So I tend to get my thrills from slick teamwork like double-plays, or fielding and throwing from the deep outfield, whoever is doing it. I also enjoy the minutiae of tactics around pitching in late innings, though my understanding, even after all these years, is superficial.

That said, there are a few outstanding players and performances I’ve seen in the flesh which stay with me: I was lucky to be in Baltimore in September 1995 when Cal Ripken Jr. broke Lou Gehrig’s consecutive game record. On that night I was working (Clinton and Gore were there) and to see Ripken achieve that feat, hitting a home run on the same night, was quite something. An iconic baseball moment.

I have a few other favourites: Albert Pujols (an alumni of the aforementioned Jayhawk League) in his pomp in St. Louis delivering a walk-off double in front of a full house at Busch; Ichiro Suzuki slapping unlikely field-splitting hits seemingly in every at-bat in Seattle. Similarly, Derek Jeter, who I saw a lot, always got hits for me. And by the eye-test I rated his fielding highly as well, though I gather sabermetricians think my eyes deceived me!

Steve: And which of the ballparks you visited really stuck out for you?

Chris: I was lucky that my baseball travels coincided with the wave of ballpark building which followed the demise of multi-purpose stadiums. I experienced a few of those concrete bowls in person before they were demolished, in Philadelphia, Cincinnati, St Louis, Minneapolis and San Diego, and they were soulless places. I have also been to their successors in those cities and there’s no doubt the fan experience is better, even if all the retro schtick can feel too manufactured and tickets are overpriced.

Of the “new” ballparks, Camden Yards remains my favourite, if only for the B&O warehouse backdrop and my memories of Ripken’s night in 1995. I also have a soft spot for Pittsburgh (with its cityscape) and San Francisco (location). I understand why people wax lyrical about Fenway and Wrigley, though I find them generally uncomfortable and with poor views.

For me, the best of them all is Dodger Stadium. Okay, you can only get to it by car, but that’s not so outlandish for LA, and it’s hard to imagine a ballpark offering a finer homage to West Coast style and glamour. For a purer vibe, I love the minor leagues. Cheap, close to the action and if you’re lucky a good giveaway: free barbeque at a Texas League game one sunny afternoon at the Wichita Wranglers was as good a ballpark experience as I’ve ever had.

The most important thing from that whole experience, though, is the friendship I formed with my road companion, Simon. We started out as work colleagues, and over the years, the miles on the road and the hours in the ballpark forged a friendship based around conversation, which is probably baseball’s biggest contribution to sports fandom.

He was my tutor on the game, the rules, the personalities, and, as far as his knowledge would take him (which was considerably further than mine). the tactical nuances. But it wasn’t only baseball we spoke about, it was America in all its flawed glory: music, culture, food, American life and politics. And if there was a soundtrack to our trips it was probably Rush Limbaugh and the hordes of right-wing radio talk-show hosts who dominated the AM airwaves.

During a long stretch on the road, their conspiracy-driven, post-truth narratives were compellingly listenable – infuriating but compulsive to our foreign ears, accustomed to the more restrained political discourse of Europe. In hindsight, the hazard lights were flashing, but to these two British baseball fans on their own American journey, the extent to which voices like those would fuel democracy-threatening party polarization was not yet apparent. Like our bobbleheads and barbeques, it was just more Americana.

*

Steve: What was the first election you voted in and what was the first US election you covered?

Chris: I first voted in 1979 – in the first of Margaret Thatcher’s three general election victories. I didn’t vote Conservative, I voted for the Liberal Party. As an 18-year-old schoolboy I was boringly centrist, pro-Europe and a member of the anti-apartheid campaign. My views haven’t changed much since – it’s just that there seem to be fewer of us centrists making noise these days.

In the US, the first election I covered was that 1992 campaign. Clinton would eventually also position himself in the centre, with his use of conservative tools (welfare reform, balanced federal budget, etc.) to meet middle class aspirations for economic equality. Sure, he was liberal on most social issues, but there was a conservative strain in there as well on crime, work and responsibility. Even with these moderate views, somehow the right managed to portray him as the enemy of American civilization. It’s still how they view him today.

*

Steve: There’s been a tremendous amount of change in both baseball and political life since then – what do you think have been the most significant shifts?

Chris: I think there’s a narrative arc that unites both baseball and politics – and that’s the erosion of symbols, institutions and ideals which once bound people together. It’s not an original insight, but the America I experience today is a fractured society – people agree on less and their disagreements are increasingly ill-tempered.

Political institutions, the media, science, Hollywood, health, sports, all find themselves sucked into the “culture wars” (a label I first encountered while covering Clinton). Unbridgeable opposing moral worldviews seem to be destroying almost all concepts of national unity. I’m not saying that MLB has been on the front line of those wars as much as the NFL, but in the ‘90s baseball was still “the national pastime” – it had the cultural power to invoke shared memories and common purposes. When it came to national values, it had heroes like Ripken that everyone could unite behind. It had moments – like the home run race of 1998 – when it grabbed the attention of everybody. It stood for something.

That cultural heft has diminished. The turn-of-the century PED scandals, labour disputes and controversies over cheating have sapped the game of its moral authority; the structure of some TV deals has denied baseball an effective national platform so the NFL dominates sports conversation. Name and logo changes, and efforts to speed-up the game to “stay relevant” have inevitably been interpreted through partisan lenses and accusations of “wokeness”. There’s little left in professional baseball that contributes to national unity.

*

Steve: You’re a big cricket fan – can you try to distil how you think both games represent the character of the countries they’re from (ignoring baseball’s dubious origin story)?

Chris: For me there are two big tensions that have shaped the development of each sport – and they reflect the character of the respective countries. In baseball the professional game we see today grew from the struggle between capital and labour to control a newly emerging entertainment industry, owners versus players in the pursuit of profit and personal enrichment. It’s still there today. The essence of American capitalism.

The culture of English cricket, on the other hand, is still defined by class. It grew out of the tension between “Gentlemen” (amateurs from the upper-classes who played and ran the game) and ”Players” (working-class professionals who served at the behest of the “Gentlemen”) – a microcosm of the British class system. Even today professional cricket clubs are still run by members with the profit motive is well down their list of priorities. Private school pupils dominate the ranks of elite English cricketers, just as they do in many British institutions. It’s true the fan base is more socially diverse thanks to short-form and franchise cricket, and women’s cricket has really benefitted with decent crowds and media coverage, but I think the game is still very much a product of the class system in terms of who plays, who succeeds and who leads.

Steve: And when you look at Bill Clinton alongside a British PM of the time – and a well-known cricket devotee – John Major, what does their respective relationships with sport say about them?

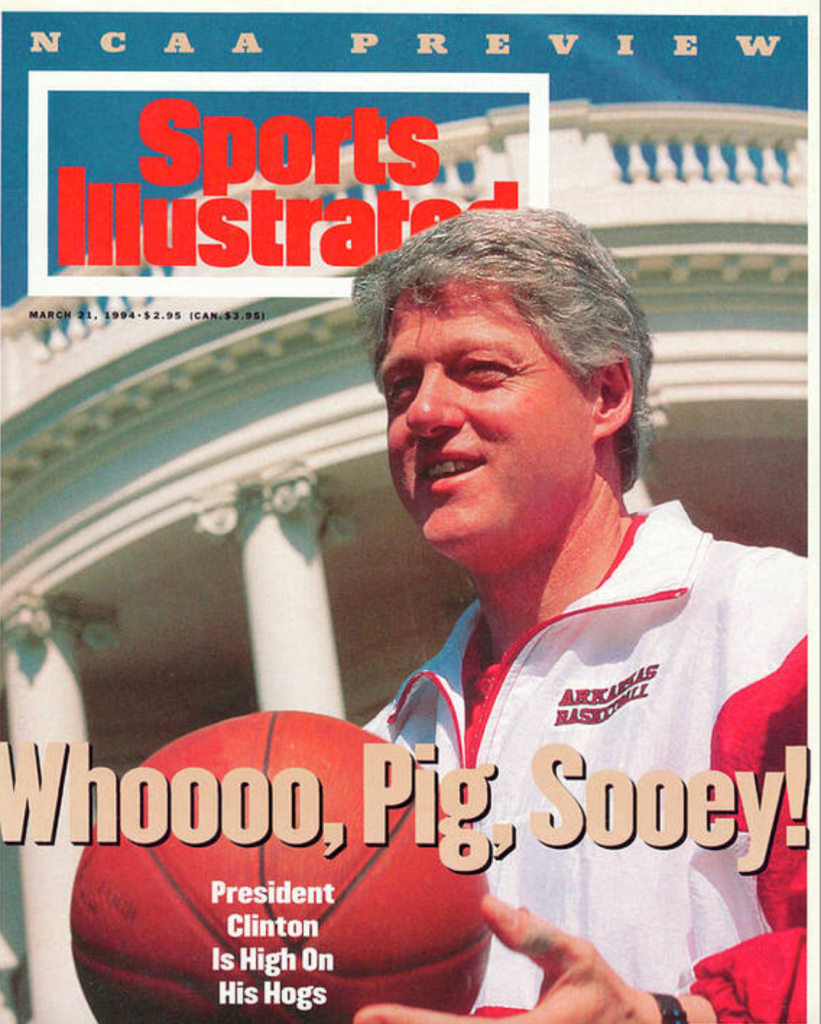

Chris: Major was the UK prime minister whose period in office most overlapped with Clinton, and though they were both big sports fans I’ve come across nothing which suggests they ever bonded over it. Of the two, only Clinton truly exploited sport for political ends. His fandom was part of his political persona – as early as 1994 he was on the cover of Sports Illustrated for a piece around college basketball titled The First Fan.

US presidents and politicians have been much less reticent about engaging with sports events and teams than their British counterparts – sport is so ubiquitous on the American cultural scene that every president since Nixon has been forced to engage with it in meaningful ways.

Major’s love of cricket, on the other hand, was always understated – cricket was his sanctuary from politics. (After leaving office he wrote a book on cricket’s early days and his embrace of the game). He’s best known for quietly shuffling off to The Oval to watch a county game on the day after he lost the 1997 general election to Tony Blair. The description in his own words says it all: “the spectators gathered there that afternoon expressed words of sympathy upon my defeat before turning to the more important matter of cricket”.

Of course, British political leaders have used sports for photo opportunities (Blair’s head tennis with Kevin Keegan or Boris Johnson’s absurd participation in a kids’ rugby game). And they’ve wrapped themselves in the flag of British sporting success on the international stage. Some have even been genuine fans (Brown, Starmer, Corbyn and Sunak are/were all season ticket holders of the football clubs they support). But they never really viewed that as a route to connecting with the electorate more broadly as in the US model – perhaps because so much British fandom is tribal in nature. You inevitably alienate more people than you attract.

Steve: At a moment when we think we might have seen it all, what innovations do you think might be coming next in sports coverage?

Chris: I think cricket has still has a fair way to go to catch up with baseball. The data-driven analytics available to fans is improving, but there’s nothing in the cricket digital universe as good as the play-by-play Gameday player in the MLB app in my opinion – great real-time graphics. As for true innovation in cricket, I’m waiting for the first live VR camera in a batter’s helmet, so we can all have the experience of ducking a Jofra Archer bouncer.

*

Steve: We’ve both been lucky – I think – that our careers spanned the entire digital and social media revolution during journalism’s most disruptive period. What are the most significant changes you’ve experienced?

Chris: They’re simply too numerous and too fundamental to list. The barriers to entry as a publisher are so low (non-existent) that the whole concept of what journalism is now has been redefined. Not a topic for a brief Q&A. So let me just highlight a couple of issues that concern me most.

Firstly, the decline of local journalism – I started off in weekly paid-for local newspapers, a species now virtually extinct in the UK. Local radio in the UK also barely survives – or at least the news/speech elements of it. Local government goes unreported; courts are not attended by journalists. There’s a serious democratic deficit here which the digital media has done nothing to address. I’m not hopeful that will change – I can’t envisage the commercial model that will reverse the trend. On a more prosaic level, even independent reporting of local sports teams is dwindling away.

Secondly – the pressure we now put on journalists to multi-task has impacted their craft skills. On any given story the young journalists I teach are expected to be newsgatherer, camera operator, video editor, producer, reporter, writer, sub-editor and publisher all rolled into one. It’s great that they are more adaptable and technically savvy than I ever was – but inevitably some of their individual skills suffer simply through lack of time.

Some observers highlight the threat to investigative journalism (which is real), but in my particular field, the most alarming development is the deterioration of writing skills – the elegance of writing, the smoothly turned phrase, the right words for the right moments. Writing is the essence of storytelling – but it’s not a skill that is nurtured enough in journalism schools or really cherished any more in the industry. AI will only make it worse. It offers a quick fix when journalists are under time pressure, and it often writes copy better than they could do themselves. But it doesn’t produce exceptional writing that makes great content stand-out.

*

Steve: How did you decide the theme of your book?

Chris: I’d wanted to write a book about the influence of sport on political culture for a long time. When I retrained as an historian in middle-age, I felt it was an overlooked area of historical scholarship, with large parts of the academy sceptical about the role of sport in historical narratives. So my book grew out of my PhD thesis. I naturally focused on Clinton who I knew was a big sports fan: I’d experienced his appropriation of a big sporting moment in Baltimore in person in September 1995; and seen him aligning himself with Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa in 1998 when the future of his presidency was on the line. Two visits to the Clinton Presidential Library in Little Rock unearthed other examples, and after I contacted a few ex-Clinton staffers who agreed to be interviewed, I knew there was a book there to be written.

But I was determined it would not only be about a president’s use of sports in political communication – I also wanted to offer a snapshot of baseball’s status in the American cultural landscape of the nineties, and its role in the search for nationally cohesive ideals and symbols at a time when many of America’s common cultural bonds were disintegrating. Clinton’s insight was in recognising what he called “the fraying” of American society: it worried him, he thought about it a lot and tried to do something about it – although you can probably say without much success in the long-run.

Steve: And what were the things that most surprised you during your research and writing?

I hadn’t done archival research before my PhD – I’d been a 24-hours news journalist, always instantly reacting to things, making rapid judgments and acting on them. Immersing myself in a presidential archive involved a totally different way of thinking and working – I’m sure investigative journalists do it, but that hadn’t been my scene. So sidebar stuff made a big impression. For instance, I hadn’t realised how much a president like Clinton drew on history, sought the advice of intellectuals and had a real grasp of competing arguments and nuance. He read a lot. He was clever. Speeches were important. He always had one eye on his legacy. I suspect today’s White House is different.

In terms of uncovering something which I hadn’t expected, I was surprised by the influence of Ken Burns within the Clinton White House. His 1994 PBS documentary series Baseball plays a large part in my book. It struck a real chord with some important people in Clinton’s communications team. Indeed, I think that the broader Burns’ articulation of American culture – his portfolio of films about the symbols and institutions which he suggests define how Americans see themselves (baseball, jazz, country music, Vietnam, National Parks, the Civil War etc.), has made a big contribution to American popular thought over the past three decades, though I fear his thesis of a unifying American myth is now in tatters.

*

Steve: How effectively do you think Presidents since Clinton have used the media?

Chris: Like all presidents, Clinton loathed the media when it was critical of him – it offered a platform for that “vast right-wing conspiracy” which Hillary railed against. TV-focused events were his main form of communication but he was obsessed by newspaper columnists, convinced that they were a barrier to getting his message through. It’s one of the reasons he was so keen on the weekly radio address – it went direct to the public, unfiltered. The radio address survived until Trump’s first term, when DJT realised that Twitter offered a much bigger reach for his unfiltered thoughts.

The norms and conventions which shaped the relationship between press and the White House did not change much in the Bush and Obama eras. Both saw the press as something to be controlled – they had comms teams which were strong on message discipline; both limited access to the president and favoured working with sympathetic outlets. Karl Rove inevitably pushed Bush towards Fox News; Obama had his spats with Fox News but they were never actually banned from the briefing room. If Obama’s White House was annoyed with a story, they were more likely to use aggressive leak enquiries, occasionally tapping the phones of journalists (as happened to the Associated Press in 2012).

That instinct to control the media by all presidents is one reason that public trust in the media across the whole population (not just Republicans) has been in steady decline since 2000 – long before Trump came on the political scene. Trump realised it and exploited it – he doesn’t try to limit access in quite the same way. Instead his instinct is to flood the zone through sympathetic content creators and not worry about whether what he’s saying is true or not – if it’s what your target audience wants to hear, then it’s good.

Meanwhile much of the legacy media fails to meet the challenge – ownership structures mean they feel compelled to defer because of other business interests; in the famous words of CBS president Les Moonves in 2016, “It may not be good for America but it’s damn good for CBS.”

There’s no doubt journalism is struggling – the combination of Trumpian post-truth in a post-trust world has created a destructive cycle. But there must be some media fightback.

For example, I find American TV interviewers exasperating, far too deferential: they lack the scepticism of their UK counterparts (Jeremy Paxman’s starting point, for example, was “why is this lying bastard lying to me?”) and the use of forensic interrogation (Andrew Neil). There are other things we could do too – some of it is up to teachers like me: train journalists better; educate the public in media literacy. But I fear it’s too late to expect democratic institutions to do anything to protect a space for non-partisan journalism – that ship sailed in the 1980s.

Steve: Given that we’ve been in a situation for a while now where literally anything could happen on any given day, how do you see this upcoming mid-term year unfolding?

Chris: Until the recent gerrymandering tit-for-tat I was confident that the Democrats would regain the House – it’s just a history thing, presidential parties nearly always struggle midterm. But if the Republicans can add a net 6-10 seats by gerrymandering it could be close. The Senate looks too much of a stretch for the Democrats. If pushed, I’d still put my money on a Democratic House: low propensity Trump voters don’t turn up if he’s not on the ballot and I think the Dems will be energised.

Most fascinating, and scary, will be to watch how Trump uses federal power in the run-up to the midterms – federal troops in Dem cities, attacks on early voting, ICE crackdowns, interference in counting/certification – we’ll see what happens. I think Trump is probably more interested in the outcome of 2026 than 2028. I don’t think he’ll try to run in 2028, and he knows if he loses the House in 2026, he’s in lame duck and aggressive oversight territory. That would trigger another monumental struggle between the branches of government.

Depressingly, I can’t predict who’ll be on the winning side, but it will be a big stress test of politicians, the media and the Constitution.

*

Steve: What are some of your personal favorite books or movies – not necessarily just baseball-related, but that’s a good place to start!

Chris: These days I do a lot of reading – it’s one of the joys of stepping off the 24-hour news treadmill. Much of it has revolved around doing a PhD and becoming an historian, so there’s a good deal of history and baseball in there. I’ve been heavily influenced by Jonathan Mahler’s Ladies and Gentlemen, The Bronx is Burning (2005), a brilliant portrait of New York in the mid-70s which juxtaposes the battle for the city’s mayorship between Ed Koch and Mario Cuomo with the story of the fraught relationship between Reggie Jackson and his highly-strung Yankees manager, Billy Martin.

It was the first time I’d come across the interweaving of political and sporting narratives to illustrate bigger themes – race, crime and urban decline.

My other must-read baseball book is Mitchell Nathanson’s A People’s History of Baseball (2012). For anyone irritated by the over-romanticised style of many baseball histories, with their focus on the game’s supposed role as the crucible of American virtues, Nathanson provides the antidote. It’s a myth-busting story about power and money. And it’s very convincing.

Paradoxically my favourite baseball film, Field of Dreams, is very much a product of that over-romanticised baseball genre. (When he was president, Clinton said it was his second favourite movie after High Noon.) All the baseball metaphors and tropes are shamelessly pumped out – fatherhood, innocence, tradition, the American dream, faith, redemption. It’s all there and I love it!

I have twice visited the site in Dyersville, Iowa, where Field of Dreams was filmed – the first time with Simon on one of our early road-trips, then seventeen years later with my son Freddy, when we emerged from the cornfields to shag flyballs on the playing field. A classic father-and-son moment experienced through baseball.

About as far away from baseball as you can get, I’ve just finished reading Richard Evans’ epic trilogy on the history of the Third Reich: The Coming of the Third Reich (2003), The Third Reich in Power (2005) and The Third Reich at War (2008). It’s an engrossing account of how a developed democracy with a vibrant cultural life fell from grace, descending first into autocracy and eventually fascism. Chilling.

*

Steve: Finally, Chris, what’s next for you? Is there another book in the pipeline?

Chris: My next book project is still at the research stage. It continues my exploration of the space where sports and politics meet, and the collapse of institutions which bind communities together. It’s got a working title, When the Gods Fled Brooklyn, and it’s a portrait of the borough in the late fifties and sixties, when the flight to the suburbs took hold and so many of its anchoring institutions disappeared – the Dodgers, the Dockyards, the daily newspaper, and much of Coney Island.

One of the book’s main characters is a property developer, one Fred Trump, Donald’s dad. I’ll just leave it at that for the time being. Hopefully I’ll complete it by 2027, in time for the 70th anniversary of the Dodgers upping sticks to Los Angeles, the original sin perpetrated on Brooklyn.

***

You might also enjoy these other Q&As from the past couple of seasons:

‘Relief’ – Danny Knobler

“The game is great and you’d love for there to never be huge, huge changes. We want it to look similar to the games we see on the old black and white newsreels. But the best changes go so smoothly you forget the game had ever been played without them.”

*

‘Go Play Catch, Kids’ – John W. Miller

“I don’t see how national politics stop being a mess. I think in the long run, the U.S. moves for a federalized system. I don’t really see how California and Alabama are still part of the same country in 2100.”

*

Blue Moon and Great Balls of Fire – John Pearson

“The only hope, I see, for any return to any form of national consensus about social and economic policies is if the Democratic Party can be clear about its values, priorities and goals and can make it clear that many of those who think Trump is the answer, would actually be better served by the Democratic Party. But I see little hope that will happen given the grave and real disagreements about the current issues facing the country.”